Americans start slipping behind on debt as delinquencies rise for car loans, credit cards and student loans

Years of relative stability end amid political and culture clashes

Total U.S. household debt hit a record $18.4 trillion this year, as consumers juggle higher borrowing costs and persistent inflation.

Delinquencies are climbing fastest in car loans, credit cards, and student debt — particularly among younger and lower-income Americans.

While mortgage payments remain largely stable, signs of strain are emerging in southern states and among nonprime borrowers.

After years of relative stability, more Americans are beginning to fall behind on their debt payments, signaling rising financial stress as the cost of living and borrowing continues to squeeze household budgets.

This week is a crucial one for the economy. Funding for the SNAP food-assistance program runs out, furloughed and fired federal workers exhaust their back-up funds and it’s make-or-break week for the stock market. Key tech companies will report their earnings later in the week; the results could dictate whether the bull market continues. There’s no end in sight for the federal government shutdown, however.

While the economy continues to burble along, there’s growing concern about the federal debt and about the total amount owed by consumers.

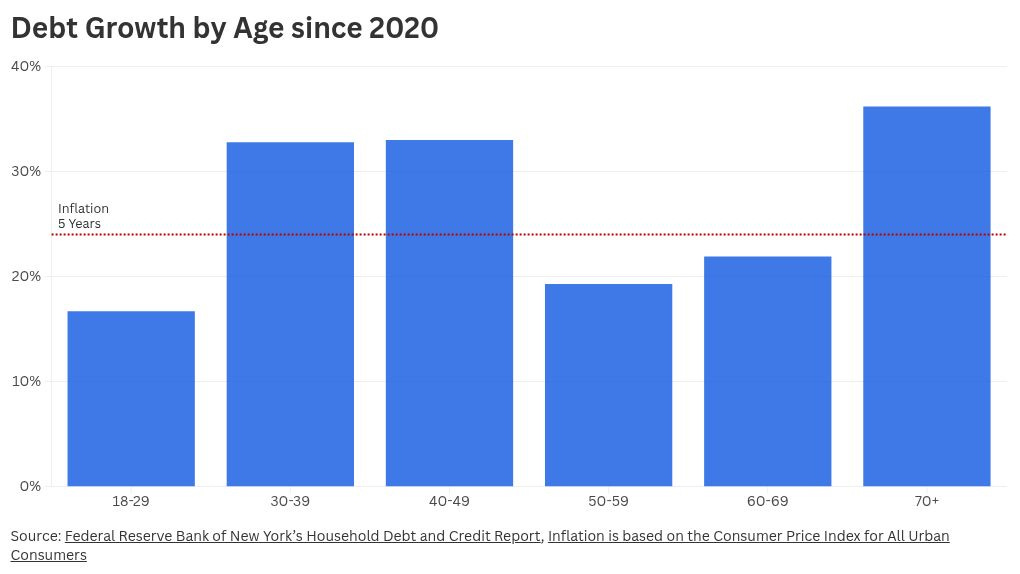

Gross national debt hit $38 trillion for the first time in history last week and total household debt reached roughly $18.4 trillion in the second quarter of 2025, according to the Federal Reserve Bank of New York — also a record high. Though most borrowers are still keeping up, data show that delinquencies on several forms of consumer credit are climbing, led by auto loans, credit cards, and student debt.

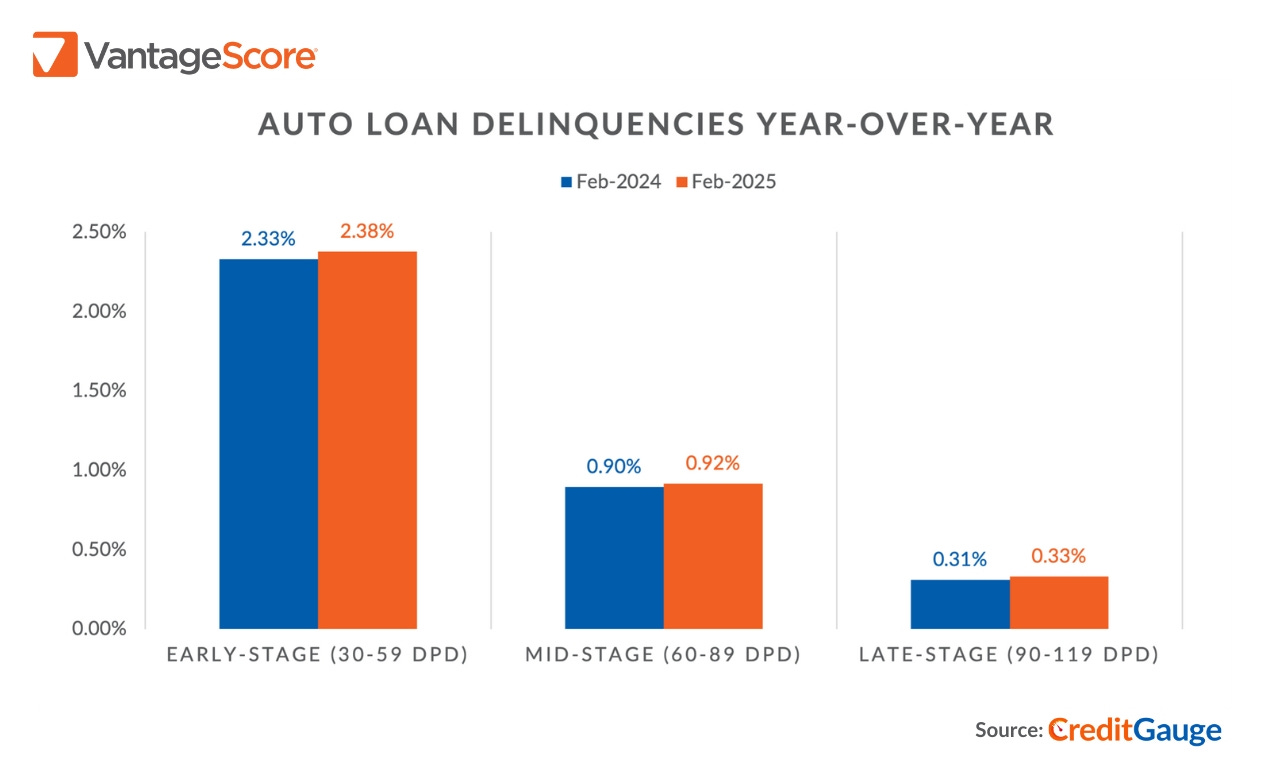

The picture is uneven across loan types. Mortgage delinquencies — the largest slice of household debt — remain near historic lows at about 1.6%, according to the Mortgage Bankers Association. But payments are beginning to slip elsewhere. About 5% of auto loans were seriously delinquent (90 days or more) this spring, up roughly 12% from a year earlier, LendingTree data show.

Credit card trouble is spreading too. Roughly 3% of card balances at commercial banks are now at least 30 days past due, according to the Federal Reserve, and nearly 12% are 90 days past due — the highest rate since before the pandemic.

Student loans have emerged as an even greater concern. With federal loan payments resumed after a three-year pause, more than one in ten borrowers are already delinquent, and millions have seen their credit scores fall, according to recent analyses from the New York Fed and Newsweek.

“These trends suggest that household finances are fraying at the edges,” said one Federal Reserve economist, noting that while most borrowers remain current, “we’re seeing distress building among younger and lower-income households.”

Who’s feeling it most

The burden isn’t spread evenly. Gen Z and millennial borrowers are showing the sharpest increases in missed payments — with delinquency rates on car loans exceeding 7% among younger drivers, compared with about 4% for Gen X, according to LendingTree.

Geographically, debt stress is concentrated in the South, where incomes tend to be lower and car dependency higher. Mississippi, Louisiana and Georgia lead the nation in auto-loan delinquencies, with nearly one in ten borrowers behind on payments.

Credit-card delinquencies, meanwhile, are climbing across the income spectrum. Even in the nation’s wealthiest ZIP codes, roughly 8% of cardholders are now delinquent — and in the lowest-income neighborhoods, that figure exceeds 22%, according to the St. Louis Fed.

Still short of a crisis

Despite the rising strain, economists say this is not yet a replay of the 2008 financial crisis. Debt-service ratios — which measure payments as a share of disposable income — remain moderate, with households spending roughly 11% of their income on debt, compared with 13% before the Great Recession.

Still, the trend lines are worrisome. “We’re seeing a clear uptick in stress indicators, especially among nonprime borrowers,” said analysts at VantageScore, noting that subprime credit-card and auto-loan delinquencies are above pre-pandemic levels.

What’s next

If inflation stays sticky and interest rates remain high, analysts warn more borrowers could slip behind — particularly those carrying variable-rate or revolving debt. But for now, strong employment and rising wages are helping many households hang on.

“The story isn’t one of collapse,” said a senior researcher at the New York Fed. “It’s one of growing strain — a slow build-up of financial pressure that could spread if the economy weakens.”