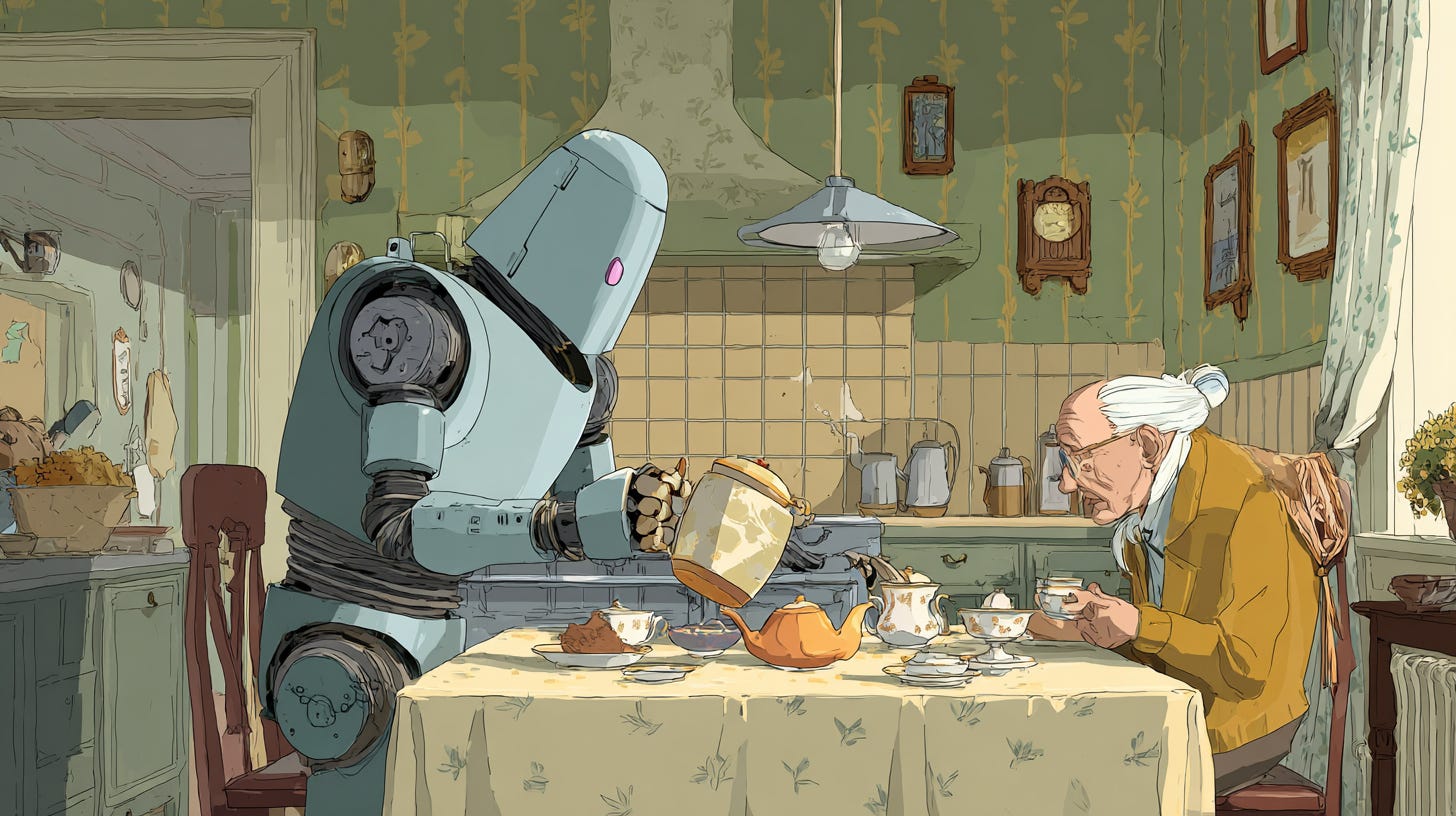

Home care for seniors may soon come from robotic sensors

When humans can't do it, technology is keeping seniors safe, or at least somewhat safe, at home

• Demand is rising and budgets shrinking, pushing tests of proactive telecare

• Home-sensor pilots in England show benefits for independence, safety and early intervention

• Researchers say five barriers must be solved before the tech becomes standard care

England’s overburdened social care system is increasingly turning to technology in hopes of keeping people safe and independent at home, and similar solutions may be in store for the U.S., as an aging population and a static or declining number of caregivers collide.

A new evaluation from the DECIDE rapid-evaluation centre — a partnership between the University of Oxford and RAND Europe — finds that home-sensor systems can help prevent crises and flag changing care needs, but also create new challenges that must be addressed before the technology becomes mainstream.

How the technology works

The “proactive telecare” model described in a recent RAND report involves installing sensors that detect movement, appliance use, room temperature, and door openings in a person’s home. The systems monitor daily patterns and alert caregivers when something looks amiss. The goal is to catch problems early, reducing distress for individuals and lowering demand on already stretched health and social care services.

DECIDE researchers worked with three English councils, interviewing 51 staff members and 19 service users or family members, and reviewing existing literature and expert input.

What the pilots revealed

Across councils, the care pathways followed a similar pattern: identifying candidates for sensor support, assessing suitability, installing the sensors (including supplying Wi-Fi if needed), monitoring and responding to alerts, reviewing usefulness, and eventually removing equipment when no longer necessary.

The systems proved especially valuable for:

More thorough assessments, providing a 24/7 picture of daily routines.

Supporting people returning from hospital, helping track whether reablement was on course.

Spotting emerging health issues, such as sleep apnea or urinary tract infections.

Informing decisions about care packages, including whether residential care might be needed.

Families often felt reassured that sensors helped preserve a relative’s independence while still keeping them safe.

The unintended downsides

Researchers also documented significant risks. False alerts disrupted routines and heightened anxiety for service users and caregivers. Some families felt unable to “switch off” because monitoring responsibilities shifted onto them. Technology failures, fears of misinterpreting data and concerns about privacy — especially for people with mental health conditions — added to resistance.

Five barriers to wider adoption

The study argues that proactive telecare will remain a niche tool unless five issues are addressed:

Funding

Most councils can only afford short-term pilots. Long-term value for money remains unproven because necessary cost-benefit data is incomplete or inaccessible.

Fragmentation

Effective telecare requires coordination between social care, health systems, industry partners and families. Current arrangements are patchy and lack formal partnership structures.

Fit within existing systems

Staff need training to interpret data and understand who is responsible for monitoring and follow-up. Technology must integrate smoothly into existing care pathways and family routines.

Incomplete picture of care needs

Sensor data cannot replace traditional assessments or the “human touch.” Overreliance may be misleading, especially when staffing shortages tempt providers to substitute technology for in-person evaluation.

Fear and trust

Privacy worries and concerns that data could be misread — potentially affecting care packages — undermine buy-in. Clear communication about why sensors are used and how data is interpreted is essential.

A promising tool, but not yet standard

The evaluation concludes that while home sensors are already benefiting some communities, “there is still a way to go” before councils can rely on them as a routine part of social care. Addressing funding, coordination, training, data interpretation and trust will determine whether proactive telecare becomes a widespread solution — or remains a promising experiment.

Implementing similar programs in the U.S. might be somewhat easier because of the less rigid regulations that basically leave senior care up to the family, if any. Or it might be more difficult because of that hands-off attitude that basically leaves seniors and families on their own, providing only the most minimal support for caregiving, child-rearing and other services that are taken for granted in most developed economies.